H Heyerlein on Unsplash

In the digital afterlife, should big tech become our cultural stewards?

Within less than 50 years, Facebook may host more profiles belonging to the deceased than the living. This analysis from Carl Öhman and David Watson, at the Oxford Internet Institute, estimates that if user-growth continues as expected, there will be 4.9 billion dead Facebook users before 2100. That’s roughly 75 times the current population of the UK. This inevitable situation forces us to confront legal, ethical, and social concerns and ask: what should happen to our data when we die?

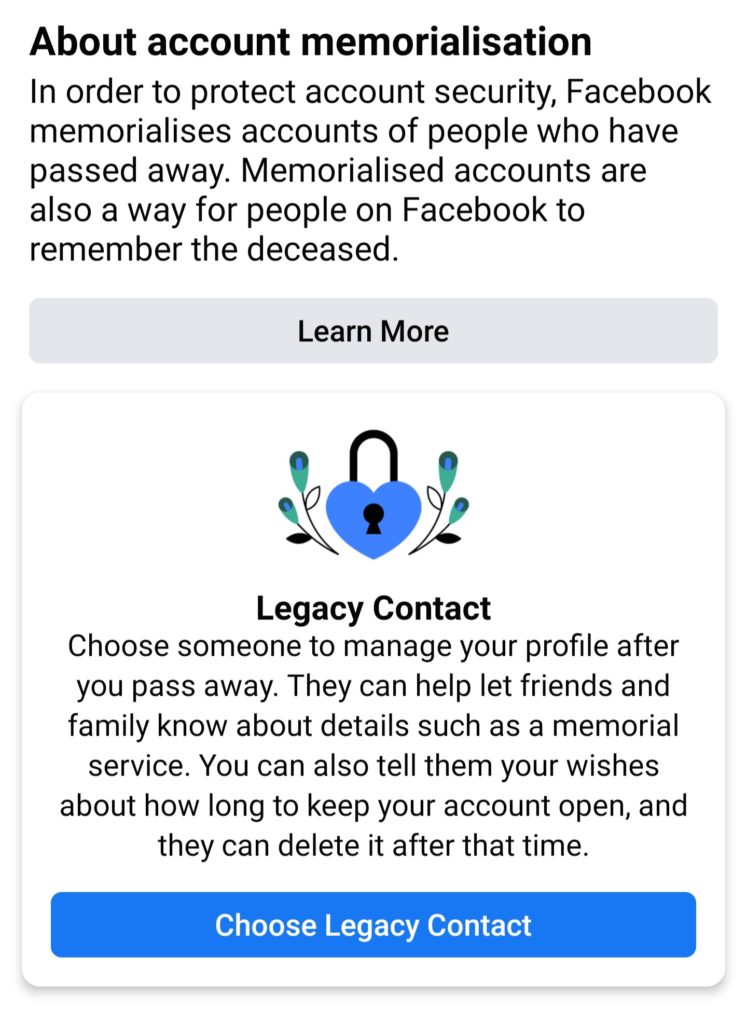

It seems likely that setting a ‘Legacy Contact’ and making a plan for your data will become one of those solemn bureaucratic tasks, like telling a loved one whether you want to be buried or cremated, opting in to organ donorship, writing a will, or taking out life-insurance. However, this all depends on Facebook’s continued existence as an entity, and users are at the mercy of Facebook not to backflip on these policies.

In the last decade, legal scholars such as Professor Jason Mazzone in 2012, and Professor Lilian Edwards with Dr Edina Harbinja in 2013, have called for data protection rights to be extended to include the deceased. Current internet privacy regulations, such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) make no such provisions.

Carl Öhman. Pic supplied

When Öhman started researching these issues in 2016, he explained that the so-called ‘digital afterlives’ landscape was more pluralistic. Many recent start-ups that offered protection or stewardship of personal data had just received seed capital. “Ironically,” Öhman commented, “all the start-ups had a name which suggested something like: eternity, saviour, footprints forever, but the vast majority failed to even get second round investment.” This is because most services developed by these start-ups were appropriated by ‘big tech’ companies such as Facebook, rendering their efforts obsolete. Facebook and others assimilating these features in-house limits the diversity of approaches when it comes to managing the data of the deceased.

In the 16 years since Facebook’s launch, the world has seen an ever-tighter enmeshing of information technology into the idea of personhood. There is now an entire generation for whom social media has always been a natural component of their self-identity, and that is unlikely to change.

As a result, social media use has turned into a far-reaching cultural practice that comes close to the equivalent of needing a bank account in your own name. More and more services require a log-in via an existing social media account, and job screenings, credit ratings, and insurance policies frequently use social media in their assessments. This near-ubiquity has forced a reckoning, the so-called ‘tech lash’, whereby mistrust and concern about privacy have engendered new regulation such as GDPR and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which came into effect in 2018 and 2020 respectively, although neither of these is yet to make provisions for the deceased.

The covid-19 pandemic has shown just how many activities can be effectively pushed into a digital format (work meetings, pub quizzes, group workouts, art classes … the list goes on), making our deep imbrication with information technology more tangible and apparent to many. In this climate the urgent need for new cultural and regulatory frameworks for coping with our digital remains is becoming clear.

Last year, one of my best friends died, aged 23. As we organised his funeral, we faced a whole slew of questions that previous generations did not have to consider, and for which there seemed little precedent. Do we post on his Facebook page? How do we unlock his phone? What do we say on social media?

This experience forced me to consider mortality alongside technology, and is a large motivator for this article. However, although I came to this piece with personal thoughts to reckon with, the answers and implications echo on a human scale. In short, do we want the most expansive and personal historical archives ever collected to be controlled by a few tech giants?

Öhman draws on precedents from the pre-digital age to see a way forward. He suggests digital remains be considered as extensions of the human body and therefore should be treated with similar guidelines to museums that hold bodily remains in their collections. The International Council of Museums Code of Professional Ethics stresses that human remains must be handled with ‘human dignity’. However, as intuitive as this is, Öhman is not optimistic about it becoming a regulatory reality. Without potential profits, what responsibility or incentive is there for these big tech companies to preserve data? Heritage museums normally have a certain amount of national funding, and even if they do not, built into the ethos of why they exist is some idea of public-facing good. For big techs, appearing to be public facing is important for PR, but is not necessarily encoded into their structures nor culture.

As of June 2020, Facebook’s help page for ‘Your Profile and Settings’ begins: ‘Your profile tells your story’. Despite the glossiness imbued into this summation, it captures how social media accounts increasingly constitute our collective histories. Nightmare versions of the future see access to these stories controlled by a limited number of profit-motivated corporate actors, who have incentive to allow access only to the highest bidder.

As such, Öhman stresses that the current discussion is too focused on individual privacy when it should be considered a long-term collective issue, saying:

“I am concerned with future generations living in a society where historical narratives are dominated by a very limited set of actors.”

Complicating the situation further is the plethora of new platforms emerging, as Gen Z abandons Facebook and Instagram for TikTok or Houseparty (and as millennials abandoned MySpace before them). TikTok, owned by Chinese parent ByteDance, has no clear procedure to request a deceased relative’s account to be deleted, while Twitter has no form of ‘memorialisation’ and regularly deletes inactive accounts. Instagram is owned by Facebook, yet differs once again: it offers memorialisation or deletion but has no ‘Legacy Contact’ feature.

We have not yet arrived at an industry standard. In which case, it is not hard to imagine a future where we have generationally-specific digital cemeteries owned by actors with varying capacities and commitments to data preservation.

Accordingly, Öhman’s forthcoming article with Nikita Agarwal of Oxford University’s Law Faculty lays out a legal and ethical analysis of what would happen if Facebook went into insolvency. One of their main concerns, says Öhman, is an administrator selling off Facebook’s assets, including the deceased’s data, to the highest bidder: “the hundreds of millions of deceased profiles that are potentially going to be on Facebook and other networks alike are extremely vulnerable in the case of insolvency. That’s something I think is a very concrete, regulatory action that we can take right now: making sure that these data don’t become commodities, that are auctioned out to potentially nefarious actors.”

This could be achieved, at least in Europe, by extending GDPR to cover the deceased. Öhman and Agarwal draw comparisons with UNESCO world heritage sites, which strike a balance between national sovereignty and human importance by asking nations to pledge to preserve a heritage site in return for funding and expert help. “We’re proposing a similar model, but in the digital realm. Firms with data archives that could potentially be of value, not only commercially but for us as a species, [would] pledge to preserve and protect that value and in return, UNESCO or some such body, would send preservation experts to the firm to help them to protect that data.”

The Clonee Data Centre, Ireland. Pic: Facebook

Last week, I added my sister as my Legacy Contact on Facebook. While this doesn’t answer any of the wider questions about who will control global history or digital world heritage, it helped me feel like I’d exerted some small amount of control over the digital extensions of myself. I would urge you to do so as well (instructions can be found in the box below). The increasing pervasiveness of big techs crystallises a need to urgently reformulate and pragmatically apply our ethics. There is no time for navel-gazing, or for allowing societies to gradually develop digital grieving practices: the stakes are too high, the change is too rapid, and the regulations are severely lacking.

How to set a ‘Legacy Contact’ on Facebook: on your profile go to Settings, then Personal information, click Manage Account and a box for Legacy Contact will appear. Type in a friend’s name and click Add. Then click Send to inform your friend that you’ve selected them as your legacy contact. More info here. Facebook’s Legacy Contact facility. Pic screenshot