Hermes Rivera on Unsplash

Fake images: How an Oxford firm’s technology is helping to verify images online

The ease with which anyone can manipulate a digital photo or video is driving an escalation in the presence of fake images across the internet. Yet technology to verify images could have unintended consequences, especially when it comes to data privacy. Oxford-based Serelay is a player in the emerging field of controlled image capture, and is part of a movement led by Adobe to build a system of trust in image verification.

Serelay’s platform, which enables rapid verification and assures user anonymity, is attracting attention from global media outlets and human rights organisations.

Media outlets in particular are often fighting tough battles to assess whether the images they are publishing are real, or have been manipulated in some way.

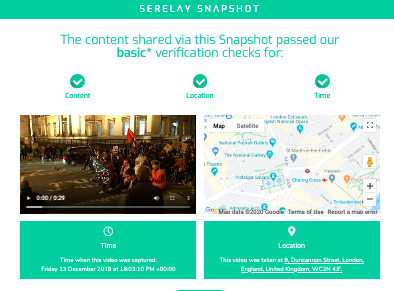

Images shot using the Serelay platform are rapidly analysed and given star ratings on the veracity of their content, where and when they were shot.

The speed at which Serelay can do this means that an image sent by a reporter’s mobile phone to a news editor can be verified and scored before it reaches the recipient. The sender installs the Serelay app on their phone, then uses it to capture the image and transmit it, either through the app or as an email attachment.

Such fast verification solves the problem of news outlets having to go through a laborious process of checks and cross-checks, which can take hours if not days.

Serelay founder and chief executive Roy Azoulay explains: “Sometimes you can look for inconsistencies in the file structure, but if a file comes off Facebook, for example, it will have been compressed,” says Serelay founder Roy Azoulay.

Questions in manual checks commonly asked are ‘Does the weather match that area on that day?’ or ‘ Does the photographer’s social media account match the location?’ For big stories, media outlets will perform forensic detection on images,“but that might be applied,” explains Azoulay, “when the New York Times, for example, knew eight days ahead it would publish a photo and can bring in an analyst to do that.”

Roy Azoulay, Founder & chief executive, Serelay. Pic supplied

While controlled capture can address the technicalities of verifying images, there are wider implications if the technology is used in isolation.

Sam Gregory is programme director for Witness, a global charity which helps people to use technology to protect and defend human rights by submitting photographic or video evidence. He welcomes controlled capture but advocates caution, saying:

“Controlled capture at source is clearly going to be part of the solution to deal with how we understand where images come from and whether they are manipulated.”

When it comes to teasing out misinformation, “We look through the lens of how people share information, whether it’s out of context, or shared in a way that confuses or deceives people, but we also need to know how to make sure these types of tools don’t have unintended consequences.”

Sam Gregory, programme director, Witness. Pic: Witness

Gregory points to the need to make sure the safety of people who are asked to use platforms or capture images in a certain way is not compromised because of the data the platforms collect, or how they might be used by governments. He is familiar with Serelay and impressed by its approach on this issue.

“Serelay have really tried to think about who controls the data, they’ve been grappling with this and have made it a central part of working out a solution,” he says.

The platform has taken Serelay three years to develop, with Google Digital News Initiative and the European Space Agency among its supporters. Azoulay describes how Serelay embedded ethics into the platform from day one, especially when it comes to data and privacy. No user data is required to download and use the app, there’s no login, password nor request for name or email.

“We think we shouldn’t need to attribute checks related to content to a named individual. If a news outlet wants to publish your image they might want your name, but that’s not a requirement of our system,” says Azoulay.

Serelay doesn’t save any photos or videos on its servers either. “With other solutions, as soon as you capture the photo, the entire input stream from your phone gets diverted to their servers. Once it’s there, if they’re asked to verify that photo eight months down the line, they can make a comparison,” Azoulay explains, adding:

“We don’t do that because we prefer not to have any photos or videos saved on our servers, and for our users, who tend to be in the media domain, it’s in their best interest if we don’t have them.”

Video analysis from a march in London, Dec 2019. Pic: Serelay

The day when anyone can check an online image, whether it’s on Facebook, a website or Instagram is far off, as Azoulay points out: “We can’t do that and no one else can. If anything it will get more difficult. Identifying manipulated content is a technically demanding and rapidly evolving challenge, so we’re working together to build better detection tools.”

Azoulay says he became involved when he realised how sophisticated fake photos and videos are becoming: “Today they often pass the ‘Extended Turing’ test, which means that neither machines nor humans can differentiate between something in the image, whether it’s a real person, fabricated or created from scratch,” he says.

He points to Facebook’s Deepfake Detection Challenge, the multi-million dollar competition designed to spur the creation of new tools to better detect when images have been altered using AI. According to Azoulay, the “best performing team now has around 75 per cent success rate, and it is not an open dataset.”

Gregory feels that right now there’s a lot of hype around deep fakes, which are costly to produce effectively, and that the real problems lie in images being used out of context or just generally misused: “The vast majority of misinformation we see is mis-contextualised. Serelay can help with that because if you can show, for example, an image was created in another time and place than [is claimed in the story it’s attached to] that’s good.”

Pic: Witness

Azoulay believes that a solution lies in not trying to verify all images on the internet, but to build a system whereby viewers know which images they can trust:

“Think about the blue checkmarks on Twitter. Only a small percentage of the Twitter population has these but you know to look for them. If I’m reading a tweet from Elon Musk, I know it’s him and not someone trying to sell me bitcoin.”

He sees something similar working for photos and videos. “If I take a shot of my son’s birthday party and I edit it, that’s OK. But if I’m photographing something of objective value, I should be able to capture that in a way that is inherently verifiable. The platforms I upload it on should quickly verify my image and tag it as such.

“Even verifying a small subset of photos and videos will, if it’s the right subset, add a huge amount of hygiene to the system.”

The Guardian news outlet is currently trialling the Serelay platform for user generated content (UGC). The site’s community journalism team is specifying Serelay’s Idem app as the preferred method of capture. Idem, free to download, contains an embedded link to The Guardian, so photos and videos sent through it are analysed during transmission and arrive at the editorial desk already verified.

“Taking the technology and seeing how we can adapt it in the real world is a challenge, and we are lucky to be able to work with The Guardian,” says Azoulay.

With more than 95 million images uploaded to Instagram daily, and around 2.2 billion users on Facebook alone, the available universe for fake images is colossal. So while Serelay seems to have cracked the technological challenge of rapidly verifying images through controlled capture, there is work to be done at an international level if the practice is going to have an impact globally.

Imaging technology giant Adobe is working with the New York Times and Twitter on a programme that could become a catalyst for just that. Its Content Authenticity Initiative is bringing industry players together to change the way metadata on images is recorded. Both Azoulay and Gregory attended the programme’s Kick Off Summit at Adobe’s San Jose HQ in January 2020.

“The idea is ambitious. They are saying we should be able to record changes we make to a file into the file’s metadata,” says Azoulay. How metadata is currently recorded on image files is a decades-old system, based on the exif format, designed by Japanese camera manufacturers. “Unless you’re a photography enthusiast it tells you everything you don’t care about – focal length, shutter speed, and so on,” he adds.

Gregory is supportive of the Adobe initiative, while stressing the need to consider the whole story: “Adobe is really starting to think about how we’re going from capture to editing and distribution.” He agrees that most images have some modification which is not malicious:

“The big challenge is that it’s not enough to say whether the originals are manipulated, but whether they are maliciously manipulated through impact and intention.”

He also warns on safety issues around creating a platform that becomes the default, as this “might backfire on people in high-risk areas who have to make decisions about sharing information, as it could compromise their safety and that of their communities.” He points out that an image confirmed taken at a certain time or place could compromise every person in it.

Azoulay sees Adobe’s track record in writing standards and successfully getting them adopted as a major factor in making this “the first serious attempt to supersede XF”.

“Most photos we see have been edited in some way, even if it’s just lightening or cropping. Once you have a way to understand how media items have changed during their life, it gives so many more possibilities,” he says.

Beyond the applications for controlled capture in the media, any organisation which handles images could use it to collect new datasets. Azoulay cites Airbnb, which has more than six million listings and 150 million users. “Often, they send professional photographers to take photos and will do some legitimate editing to improve aesthetics. But now they don’t have a way to link changes made to photos to metrics such as review satisfactions, or customers’ perceptions of how accurate the listings were.” With Airbnb listings averaging from 10 to 30 photos each, Azoulay sees this as “a huge black hole in their database.”

There’s little doubt that more scrutiny from the wider public in how we share and view images could go a long way towards cracking the fake image problem. Gregory refers to the advice Witness gives on what to look out for when using an app, urging people to ask questions like whether they trust the developer and where it’s downloaded from, is data and metadata stored and how, and is the media is encrypted. While this is potentially life-saving advice for people in areas of conflict, it’s also a valuable checklist for anyone sharing images online.

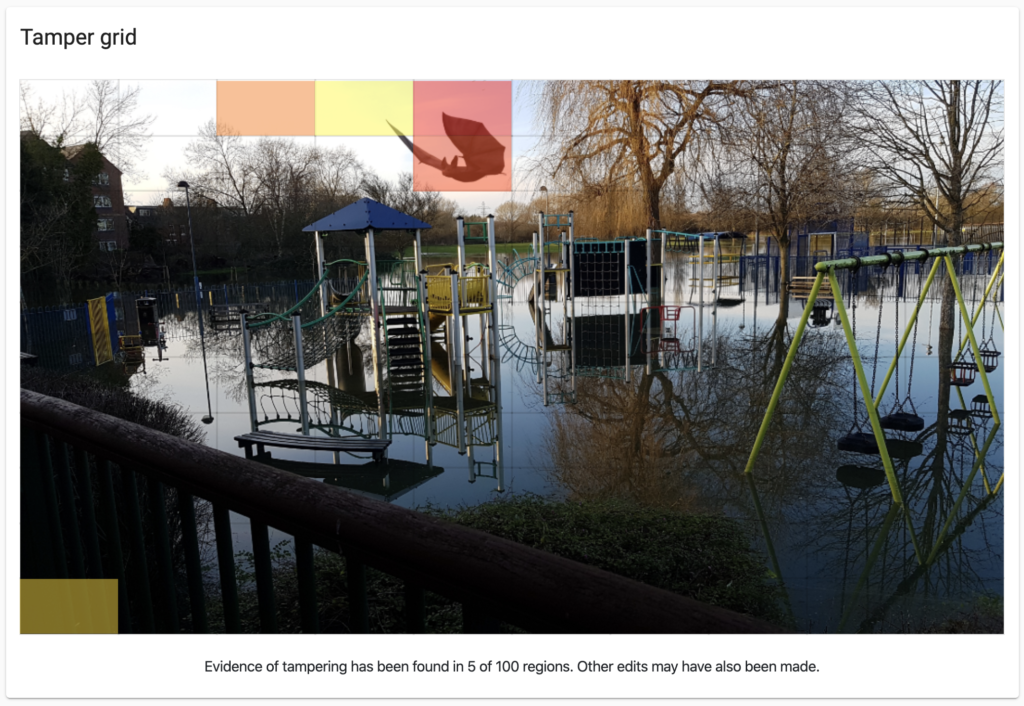

What’s wrong with the picture? How Serelay checks an image This flooded playground is attracting unusual wildlife. Pic: Serelay In a few seconds Serelay analyses an image and makes assessments in three categories, and these often incorporate some level of discretion. The platform generates a score in each of the categories and a detailed report. Serelay detects where additions have been made. Pic: Serelay Content – Has any pixel changed and what is the nature of the image? Is the photo a real, 3D image or a photo of a photo? The lossless nature of jpegs means that any additions to pixels will create changes elsewhere in the image, so noise in one part of the image could indicate or confirm manipulation in another part. Location – Are the signals from the device consistent with its location, ie, is the cell tower reading consistent with the GPS? There might be several GPS readings if the content was streamed, which could affect location accuracy and Serelay is able to analyse convergence patterns and detect whether the location is real or possibly created by mock location software. Time – Does the hour and the day match the image? Visual checks on time are carried out for users of the dashboard-based platform. The original playground shot. Pic: Serelay