Reforming Oxfordshire’s transport network: Time for the Oxford Metro?

The innovation powerhouse that is Oxfordshire will be vitally important in creating technology and knowledge economy jobs for the whole country. The county has committed to adding 100,000 new homes for the people who are going to contribute to this, but Oxfordshire’s transport infrastructure is already overwhelmed, not least in its medieval city centre. TechTribe Oxford investigates whether the timing is right for the region to revisit a project that has been tabled for many years, to include a tram or light railway network as part of an integrated transport solution.

The city and Oxfordshire’s towns are surrounded by pleasant rural environments, a feature that adds to the attraction for newcomer employees. Striking a balance between preserving this and meeting the demand for growth is a major, long term challenge for planners.

Oxfordshire County Council’s Connecting Oxford visionary report, published in September 2019, had ‘A better, faster and more comprehensive public transport network’ for the region as the first component of its plan to transform how people travel to and within Oxford, and make the city less congested and polluted.

The report estimated 220,000 vehicle miles are driven in and around the city by around 45,000 vehicles every morning during rush hour, emitting around 50 tonnes of CO2. The average morning rush hour inbound traffic speed in Oxford in 2018 was 10.6 mph and this reduced further in 2019. Average bus speeds in Oxford have been under 10 mph since 2016. More than 150,000 vehicles cross Oxford’s ring road each day, 81% of which are private cars. Around 75% of local air pollution in Oxford comes from traffic. Nationally, it is estimated that around 40,000 people die prematurely each year as a result of air pollution.

Oxfordshire County Council concluded that getting people out of cars to walk, cycle or use public transport is the answer, and proposed a number of ways to achieve that. However its solutions derived solely from the existing mix of transport options and included the concept of introducing ‘bus gates’ to speed up bus transit during busy hours.

Meanwhile the vehicle numbers, traffic speeds and pollution levels in the Connecting Oxford report look set to return as lockdown restrictions are eased, unless something radical is done.

Much time and energy has been spent looking into alternatives to simply building more roads, or making marginal alterations to existing schemes, each one subjected to lengthy consultation periods. On Oxfordshire County Council’s website there are 158 pages of consultations and, at the time of writing, 16 of the 21 consultations currently open were transport-related and addressed largely small scale changes like cycle parking, traffic calming measures and lowering speed limits. While these schemes are no doubt important, and the wheels of local government must turn, progress seems snail-paced, and attention on a long-term, environmentally-sustainable vision for the region severely lacking.

One of the most promising proposals is for a tram, or light rail network to form the spine of an integrated, multi-modal ‘Oxford Metro’ network. Perhaps the climate emergency, which Oxfordshire authorities declared in 2019 and has raised over £100 million to address, could be the trigger for a reassessment of priorities.

Oxford has had a tram system before. Horse-drawn trams provided a service, which started in 1881, from the railway station via the High Street up Cowley Road to the junction with Magdalen Street. In the following years several other routes were added. By 1910 its fleet comprised 19 double-deck trams and it had 150 horses. Its depot and stables were off Leopold Street.

Horse-drawn tram in Oxford 1913. Pic: Creative Commons.

Trams ran on a narrow four-foot gauge and were timetabled to run every 15 to 30 minutes. A horse drawn bus network was added to serve the parts of Oxford that the trams did not reach.

An initiative to introduce electric trams in the first decade of the twentieth century foundered. Trams in use elsewhere had a four-foot, 8.5-inch gauge; this meant that the track would have to be relaid. And although no overhead wires were proposed – power was to be delivered through a third track in the road – electrification was opposed by Oxford academics. The Oxford Tramways Bill 1906 was passed in Parliament, but powers under this lapsed in 1912 before the scheme could be revived, and before long motor vehicles prevailed.

Two reports for Oxford Futures from the URBED Trust (Urbanism Environment and Design), a consultancy that worked with Oxford University’s Transport Studies Unit, in 2015 and 2019, put forward suggestions about using trams or light railways as part of an integrated solution that could move significant amounts of traffic off the roads and connect new housing developments and businesses. Interesting comparisons were drawn with the experiences of similar sized university cities such as Grenoble in France and Leiden in the Netherlands, both of which have successfully transformed their localities with trams or light railways integrated into their transport systems.

Tram as part of an integrated system in Grenoble. Pic: URBED

The 2015 report recommended development should be concentrated around existing and new stations on the local rail network in central Oxfordshire and Oxford, including a re-opened Cowley branch, and on the 200 acres of under-used land around a rebuilt central Oxford railway station. Frequent and fast local rail services will take traffic from congested roads and form the core of an integrated public transport network for central Oxfordshire. This was named the ‘Oxford Metro’.

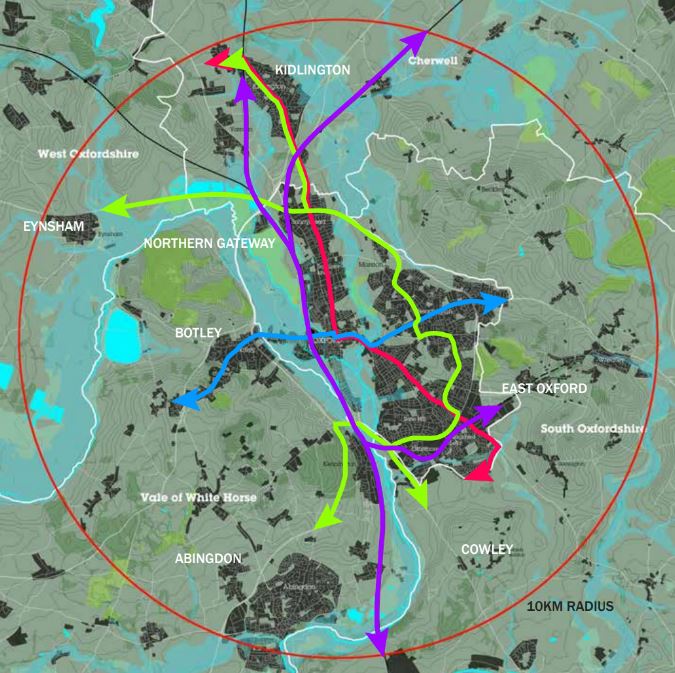

Over time, main bus routes serving the city would be upgraded to ‘rapid transit’, and the city’s first tram line (in blue on the map) would be built from Botley to the Headington hospitals and university campuses. Subsequent connections would be made for Kidlington via the Banbury Road to Botley and Blackbird Leys (red), and later a route (green) from Eynsham through eastern and southern parts of the city. Extensions to the existing rail network to Cowley, utilising existing track, and the airport at Kidlington would complete the network.

Possible Oxford Metro plan. Pic: URBED

Dr Nick Falk, executive director of the URBED Trust and author of the URBED reports, said:

“In France and Germany less weight is placed on cost benefit analysis and more on how transport projects contribute to overall wellbeing. An important factor is often connecting up a disadvantaged area, or getting cars out of the city centre. Half the costs tend to involve changing road surfaces and relocating services, so the tram is best seen as part of a general upgrade of the centre. Carbon emissions, noise and pollution more generally all matter, as does the impact on investment generally.”

Dr Nick Falk. Pic: supplied

For Oxford, if metrics such as air quality improvements, impacts on accessibility and improvements in visitor experience are given weight and factored into cost-benefit analyses, the schemes are likely to become more attractive to investors, policymakers and the public.

One common thread, though, is the focus on land value uplift as a source of capital to fund infrastructure development. This is particularly relevant in the UK, where property values are high. There is a range of ways for local authorities to derive funds from this framework. The fixity of rails instills confidence for businesses about future availability in a way that no bus timetable can. While no one would suggest that the scale of this increase could be matched in Oxfordshire, in the London Docklands, land values in the Isle of Dogs rose from £70,000 an acre in 1981 to £4.9m per acre by the time the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) opened in 1987.

Taxes can be levied on land that benefits from developments, framed as the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL). However, Llelwyn Morgan, head of innovation at Oxford County Council, says: “it is very hard to do this under the new regulations surrounding developer contributions, CIL regulations have made this much harder to achieve than previously”.

Llelwyn also observes that the baseline for the viability of housing developments has also shifted significantly. Whereas developers achieving ten percent margins could expect to raise capital readily before 2008, nowadays 20% is closer to the norm. This difference removes a substantial sum from what could otherwise become a contribution to infrastructure development. This is an area in which government intervention may be required to rebalance the allocation of cost.

In the USA, Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is widely used: this hypothecates increases in property taxes over a lengthy period, 20-25 years typically, to pay down loans used to finance infrastructure developments that cause uplifts in land value for the designated areas.

Tramlink Nottingham, which has done much to reduce traffic in the city and improve the urban environment, raised part of its funding through charging city centre businesses – with their support – for their car parking spaces.

The final element of funding, much of which is usually allocated to covering operating expenses, are the fares paid by travellers. As with TIF, a proportion of these can be set aside over a number of years to repay loans.

Cambridge has similar challenges (see boxed item). In 2016, a report by Connecting Cambridgeshire assessed the feasibility of a mass transit network, and concluded that the number of passenger journeys it would attract would be less than the commercially viable number needed to support a tram/light rail solution.

The government has channeled very significant sums into start-ups and R&D in Oxfordshire and received a good return on this in the form of jobs and foreign earnings. If it needs to rely on the county to continue to grow these contributions, it may well get the best value for its money by helping to invest in the region’s transport infrastructure. For local contributors, perhaps it’s time to ask whether the benefits it would deliver have not been defined widely enough.

Modern tram/light railway infrastructure costs around £30m per kilometer. The cost of a project to deliver 30 kilometers of track in phases will approach a billion pounds by the time it is completed, and that’s without taking into account the disruption the works would create over several years.

The presence of a decent transport system anchored around a tram or light railway network is promoted as a stimulant to inward investment. It is said, for example, that the Media City development at Salford Quays in Manchester and centred around the BBC’s decision to establish itself there, was predicated on the extension that connects it to that city’s Metrolink network. More emphatically, the first line of the DLR, which cost £77 million to build in the 1980’s, is credited with enabling the development of Canary Wharf and the regeneration of London Docklands to today’s global centre for business and finance.

In Oxford, a tram network could offer a number of advantages over buses. Modern trams are unobtrusive, because they can run on batteries in urban centres, as they do in Nice, eliminating the need for overhead cables. A tram with a single driver can move up to 300 passengers, they are quieter, and steel wheels on steel rails do not create the pollutants that rubber tyres do. Because trams are tied to rails, they require less space than buses. In narrow streets like Oxford’s, this means that space can be reallocated to pedestrians, cyclists or café tables.

Recent technology offers ways to reduce costs and speed up deployment. Battery-powered trams can have charging points embedded in the road at stops, which are only energised when the tram is stationary. Such a system, made by transport manufacturer Alstom for the city of Bordeaux, had a shaky start but is now working reliably.

In Potsdam, Germany, the world’s first autonomous tram service was launched in June 2020. Using radar, lidar (light from a laser), and camera sensors to monitor its surroundings, the tram reacts to trackside signals and responds to hazards faster than a human driver could.

Tram-train dual-mode vehicles have now been developed that can run on mainline rail track as well as on tram track. An example can be found on the track between Meadowhall South, in Sheffield, and Rotherham Central. This opens the way to using existing tracks, for example between Oxford and Didcot to join to, and extend the tram network. Although Network Rail and the UK train operators are primarily concerned with freight and long distance travel, if as part of such a project, they were able to raise funds from land they own (such as the 200 under-used acres around Oxford station), they would be motivated to engage.

Because it concluded that a conventional tram/light rail solution would not be commercially viable, the city of Cambridge looked at other options.

Connecting Cambridgeshire, a 2018 report that looked at that county’s transport challenges, proposed an autonomously operated, battery powered, guided bus system known as AVRT (Advanced Vehicle Rapid Transit). This has the advantage of lower infrastructure and operational costs. On the downside, it requires technology not yet developed and precludes ‘through journeys’ requiring travelers to change vehicles at hubs. Also, the rubber tyres contribute to particulate pollution in a way that steel wheels on rails do not.

Concept image from the Affordable Mass Transit for Cambridge and the Wider Region report by Prof. John Miles, University of Cambridge, for Smart Cambridge, supported by Greater Cambridge Partnership and Cambridge Ahead.

The Cambridge proposal includes tunnels for some urban sections of the routes. Cambridge sits on clay, an ideal medium for tunnelling and there is a huge body of technical experience in this field in the UK. The proposal points out that its proposed solution might also be suitable for Oxford and Milton Keynes but acknowledges that a development phase for the vehicles would be a necessary first stage, extending the time taken to bring a solution to fruition.

Later this year, the government has said it will produce a report on the decarbonisation of transport. In a scoping document, it sets out the challenge for what a net zero transport system should provide:

- Public transport and active travel will be the natural first choice for daily activities. Less car use and improved reliance on a convenient, cost-effective and coherent public transport network.

- All road vehicles to be zero emission. Technological advances, including new modes of transport and mobility innovation, will change the way vehicles are used.

- Goods to be delivered through an integrated, efficient and sustainable delivery system.

- Clean, place-based solutions to meet the needs of local people. Changes and leadership at a local level to make an important contribution to reducing national greenhouse gas emissions.

- The UK to become an internationally recognised leader in environmentally sustainable, low carbon technology and innovation in transport.

- Leadership in the development of sustainable biofuels, hybrid and electric aircraft to lessen and remove the impact of aviation on the environment and by 2050, zero emission ships will be commonplace.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that what the government does or does not do will affect the ease with which Oxfordshire can revolutionise its transport systems. In European university cities which have successfully introduced tram/light rail infrastructure, the leadership of local mayors has often provided the necessary focus for the efforts required.

With its five local councils and a county council holding the budget and responsibility for transport, Oxfordshire’s political structures present an additional layer of complexity. Residents could be forgiven for observing that the enthusiasm and energy for consultations, reports, visions, policies and strategies is not always matched by the leadership and creative thinking to get them enacted.

The leadership and focus required to bring a long term project like this to fruition likely depends on the establishment of a development corporation or similar organisation to bring together the relevant parties. Recent and evolving technologies can undoubtedly bring value, but the primary obstacles appear to be financial and political.